Delhi, India 1858

When the British troops entered India in 1858, they had an oddly specific (but very serious) problem with the wildlife there. Cobras were everywhere.

So the British Crown devised a bounty system – bring in a dead cobra and you get paid. Simple. And the Indian population did just that. They were killing lots of cobras, bringing them in, and the Brits made good on their bounty payment promise. The program was seemingly a smashing success.

But then one day the Brits were out in the countryside of Delhi and came across something peculiar – a cobra farm.

Yes, that’s right. A farm for breeding cobras. Enterprising Indians, incentivized by the bounty system, had started farming cobras.

Completely outraged, the British shut down the cobra reward system. But then what do you think happened to all of those snakes in the cobra farms?

That’s right! They were released into the wild. And Delhi, thanks to the cobra bounty, now had even more cobras than it had before the British arrived.

This story gave rise to what is called the Cobra Effect, also known as “the Law of Unintended Consequences”. There are countless examples of this law in action.

Here’s a list of a few really interesting ones:

- In the 1860s, the U.S. paid railroad builders by the mile of track laid. So the Union Pacific Railroad would lengthen their sections by forming a bow shape and unnecessarily adding miles of track.

- The Endangered Species Act of 1973 tried to protect wildlife by preventing development on land where endangered animals were found. This encouraged the preemptive destruction of habitats by its owners, who worried they would lose the development-friendliness of the land. Even some endangered animals were killed so they wouldn’t be found.

- In 2002, British officials in Afghanistan started a program offering Afghan poppy farmers $700/acre to destroy their poppy crops. So the population responded by having a poppy-growing frenzy to plant as many poppies as they could. Many farmers harvested the sap before destroying the plant, which means they were paid twice for the same crop.

- In 2010, a website called DecorMyEyes.com found that by shipping poorly made products, having customers complain about them, and responding with insults, threats, and violence, would actually drive more people to the site and further increased its rankings on Google. This perpetuated the company’s sales.

To make the Cobra Effect even more personal, it’s also useful to take a glance at some of the ways it can impact our careers…

The Unintended Consequence of Being Promoted

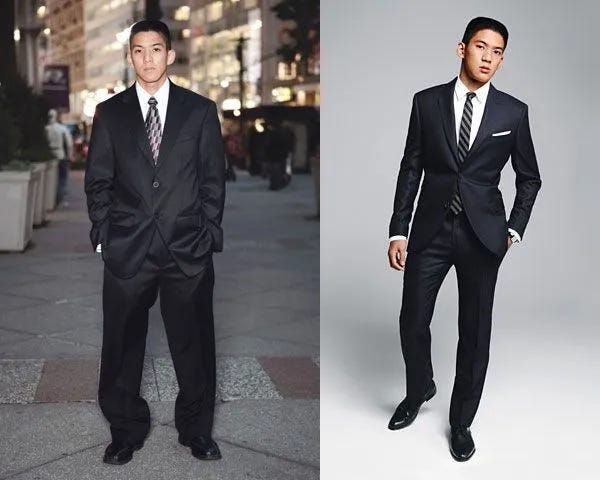

Many people try to push hard for a raise or promotion (40% of Millennials expect a promotion every 1-2 years), only to be surprised when they are in over their heads, receive unsatisfactory reviews, or are laid off. They can even (unintentionally) change their behavior and mannersims in order to match the expectations of their new status.

This is tough for people to understand, as we mostly all have aspirations to make more money, feel like we’re progressing, and like being rewarded for our work.

I remember having a coworker who would document her contributions to our company in terms of dollars added or saved, and when she took it to the CFO, his remarks were surprising. He said “Every hire we do should be contributing 5x the revenue of their salary. If anything you are underperforming relative to what you are paid.” This was surprising to her and, while she still got her promotion, she was mindful of the expectations set forth by that CFO.

Also, if you have high aspirations for your career, you should benchmark yourself against your peers in terms of work experience and responsibility. It is typically rare in business to be a people leader within your first five years of full-time work experience, for example. Doing this may show areas you should focus on to merit your next big promotion.

The Unintended Consequence of Choosing Your Title/Job First

People sometimes choose their title/job instead of their company. For example, you may be so excited to finally be a Project Manager, only to discover that the company you joined is in decline and you now have to do the job of ten people.

We generally recommend choosing your company first and your title/position second. The latter can be more fluid and you can grow/adapt within your company, but your company is going to stay constant. The company represents the culture you’re joining. Also the size of the company you join matters a lot, which you can read more about in S, M, or L? – Picking the Right Company Size for Your Career.

To further illustrate this point, when describing our career histories this is how it normally goes:

- Austin: I worked for Deloitte and managed some really interesting projects.

- Jason: I worked at Traeger and knew a lot about the grilling industry.

Do either one of us talk about our specific job titles? No! Just think about your work history and how you recount it, and then put yourself in a recruiters’ shoes – they are often looking for someone with necessary skills that has been in a similar type of company before. Choose your company first and your title/job second.

The Unintended Consequence of Overpromising

Many people will make a promise on a deadline or major deliverable, only to find themselves without the means to complete it adequately. If you do this, it then reflects poorly on you (“deadline misser”), when you had the power from the beginning to set your own timeline.

We have found it far better to wait on setting a deadline until you have properly scoped it out. Then set a realistic timeline and then deliver at or before then.

In the famous book Never Split the Difference, Chris Voss argues that time is always the most negotiable part of any deal. As an FBI agent, if he’s negotiating a hostage deal and they have set a day/time to get their money, he argues that is the most fluid part of any negotiation. Most deadlines are arbitrary and self-imposed.

Be the person that under-promises and over-delivers. Not the other way around.

Conclusion

There are all sorts of unintended consequences around us, and the trick is to spot them and think through the long tail of your decision.

…and if it’s a cobra tail, just let it go.