Too many of us simply “take the best offer” in our careers. This isn’t a terrible strategy, except for the fact that it risks delaying (potentially for years) what we really want.

My First “Big Boy” Job Offer

I had just wrapped up a 3-month internship working as an engineer for Boeing (one of the world’s largest airplane manufacturers) in the company’s enormous manufacturing headquarters in Everett, Washington (just a little north of Seattle).

Boeing was a seriously impressive company. Their Everett facility was the single largest building (by volume) in the world; big enough to hold all of Disney World within the 4 walls. One of the other engineers told me that a few years previously they actually had to install a climate control system, because the building was so large that clouds had started to form near the ceiling and they literally had rain indoors!

The corridors of the building were so long that most people took ~20 minutes to walk from one meeting to another. It was pretty common to see people biking indoors to cut down the time.

I was assigned to work on the 767 team, helping them prep the factory to build a large order of freighter planes for FedEx. I spent a lot of my time simply learning how thousands of parts came together to form an airplane. It really is an economic miracle (fun fact I learned: the average Boeing 767 costs ~$XXX). My office literally looked out onto the manufacturing floor where I could see the planes coming together in real time.

It was quite frankly the first “big boy” job I’d ever had. My prior experiences had been things like working as a cook at Dairy Queen and doing landscaping in high school. Compared to those, being an aerospace engineer (even for a summer) was quite an eye opening experience.

On my last day of the internship, my manager pulled me into his office and told me that the team had been impressed with my work and wanted to hire me to come back full-time after I finished my senior year at BYU. The salary was ~$75K/year (which at the time was more money than I’d ever been offered in my life). I shook his hand and told him I was definitely interested and would let him know my decision in a week or so.

I packed up my 1997 Honda Civic and started the long (14 hour) drive back to Utah.

And that’s when I made a decision that changed my life.

The Insight of August 2012

I spent countless hours thinking about what my future would hold in regards to these 2 important milestones in my life. At times I agonized over them. There were a lot of journaling sessions, walks by myself along the Washington coastline, and nights spent down on my knees in prayer. Despite my effort I felt like I was hitting a brick wall. No answers appeared, and I felt increasingly anxious and frustrated. I felt a ton of pressure to figure this out, and felt that I was somewhat paralyzed until I did so.

This long preparation was the state of my mind when I decided that instead of going straight back home to Utah I would take a slight detour to Corvallis, Oregon to visit my Uncle Mike. Mike was the only person in my family who had ever gotten an MBA / built a career in business (a path I was thinking about following) and I had gained a deep respect for his wisdom and insight and was hoping to have a conversation with him regarding my career.

After some fun and games with my cousins, Mike and I finally found a quiet moment to sit together in his office and discuss.

”Tell me about your plans” Mike began. I began telling him about the Boeing offer and how I thought it might be a great idea to move up to Seattle and take the job, work for a couple of years, and then pursue an MBA at a top 10 school and then work for 2-3 years at a consulting firm like McKinsey or Bain before moving on to something else. I thought my plan sounded pretty rational.

”So what’s after McKinsey?” Mike asked. I told him that I honestly didn’t know.

His next question was: “How much do you want to be a consultant?”. Mike then took a few minutes to explain what the life of a consultant might be (based on what he had noticed from several of his good friends who took that road). He told me that consulting would involve heavy work hours, a very high salary, long times away from the family, a very “posh” social circle (rubbing elbows with the industry elite) and a sense of being important and solving really complicated problems.

As he talked, some of those things seemed enticing, but others not so much. Mike then asked me: “Austin, what do you really want?”

I didn’t know how to respond. In my mind my plan had seemed so reasonable, but now I wasn’t as sure.

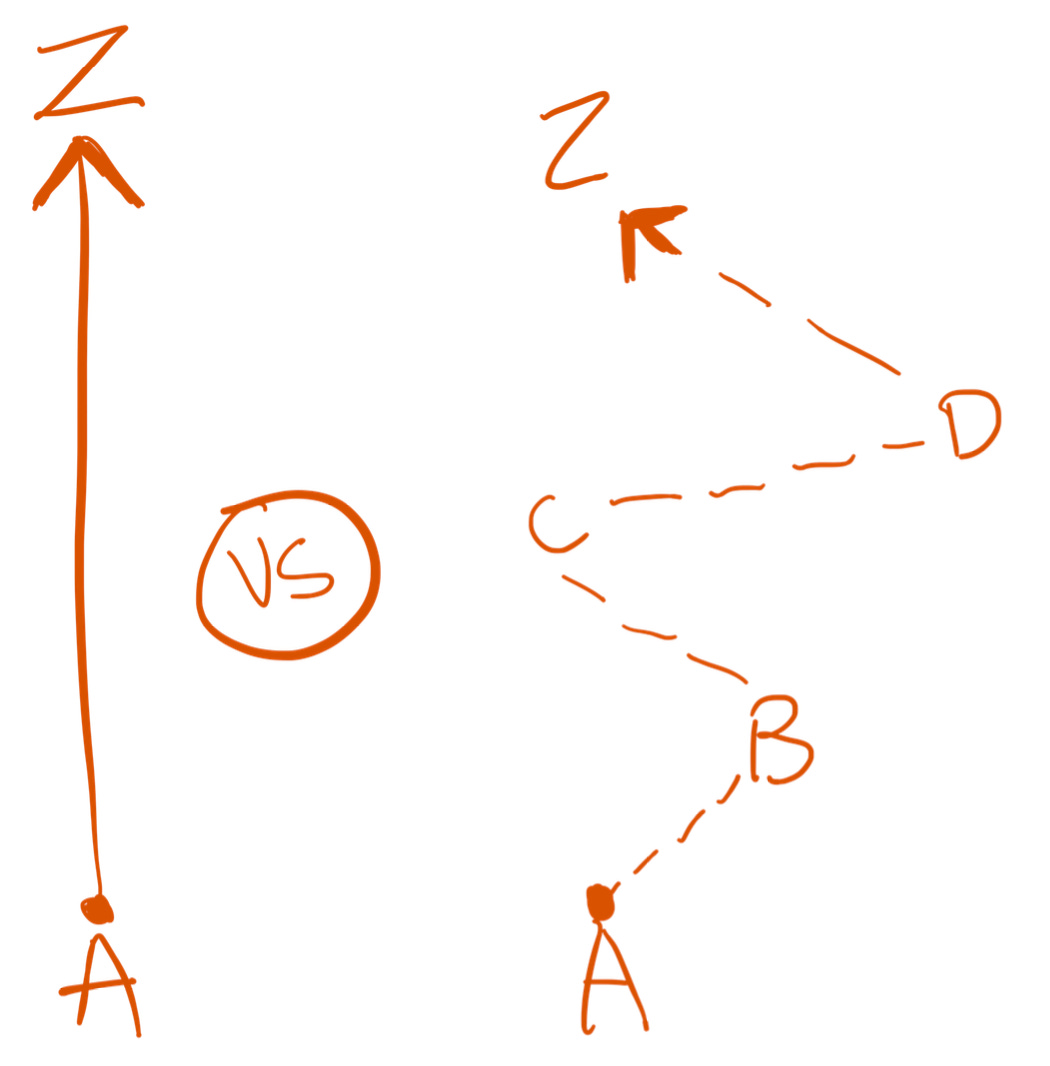

He then asked me a very simple question: “Do you know what the shortest distance between two points is?”

“That’s easy,” I said. “It’s a straight line”.

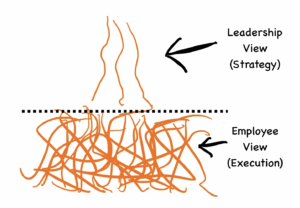

“Right!” He said. “Most people spend their lives just going from point A to B to C etc. without ever thinking about what the last point (Point Z) is. They don’t begin with the end in mind. This is actually really tragic when you see it play out in real life. If someone doesn’t know what their Point Z, their dream career, is, then they can literally waste years doing things that are rational on paper, but are actually detours to their real dream. So for example, if you don’t know what comes after consulting, I would question if spending several years at Boeing or McKinsey is really going to take you to where you want or if it’s just a very enticing distraction.”

Mike then asked me again: “Austin, what do YOU really want?”

I began to explain how my dream lifestyle would include time. Time to spend with my wife and children. To be at their games and events. Time to spend 1:1 time with my wife. And time to spend serving in my church (something that was important to me).

I also told him how I wanted to make enough money to be able to travel, have a nice comfortable home, and to ensure my family would be provided for. How I wanted to work in the tech space (something I loved reading about) and eventually be part of a small-ish company building something really important for the world (rather than be part of a large organization)

As I talked, I also realized that there were some things I didn’t care as much about: I didn’t care about being an engineer or working on very technical problems (as they weren’t the kind that really intellectually stimulated me). I didn’t care much about being in “posh” social circles, or having a lot of status or fame. And surprisingly, I didn’t even feel the need to work at a well known company.

As I finished my explanation, Mike looked at me and said slowly “so in other words, you know what you want. You know, at least in part, what your point Z is.”

“Yeah, I guess I do.” I admitted.

At that moment I knew then and there I needed to do 2 things: First, to turn down the Boeing offer & get into an MBA program (so I could transition to business instead of remaining in engineering). Second, I needed to spend a lot more time sharpening my understanding of what my personal Point Z was (as I still didn’t have a complete answer).

It was a decision I’ve never regretted.

Finding Point Z for yourself

So many of us get seduced by the siren song of a big job offer that promises more money than we’ve ever made working for a company our parents and friends know well. I’ve noticed this is especially true of people who think they want to work in consulting, venture capital, investment banking, or private equity (and similarly prestigious roles)

In each case I try to warn them, as my uncle Mike warned me, against falling for detours (no matter how attractive they may appear). The only way to really guard against that is to find our own “Point Z”.

There are a lot of approaches for doing this, but the one that I recommend to most people is the approach I’ve taken myself. There’s more here than I can describe in a short essay, but here’s the basic idea:

First, take time to write down your “career obituary”. Write out a very detailed retirement letter that reflects on what you did over the past 30-40 years of your career. Describe what kind of problems you solved, the industry you worked in, what your day-to-day life was like, what kinds of roles you had, etc. Be as detailed as possible. Even if you don’t have all the answers, write what feels authentically exciting to you instead of just writing what you feel is “most rational”. Too many of us sacrifice our dreams on the altar of rationality. I’ve found there to be great insight in writing my thoughts down on paper.

You will go back and iterate on this document often as you gain more insight (and as your desires change over time). It also won’t come all at once. My own initial “Point Z” probably took me 3-4 years of concentrated effort to get right, and it’s honestly still not complete. Many people ask me what I want to do after I (one day) leave my current role at Weave, and to be frank I still haven’t 100% determined that yet. I still spend regular time sharpening what I want my life’s career to end up as, even though I’m 10+ years into my career.

Second, share your “career vision” with mentors. Find a personal board of directors that can do for you what Uncle Mike did for me: help you think through your options and question your reasoning/strategy. Ideally these are people who have successfully built careers similar to ones you think you may enjoy, who are invested in your success, and are willing to be candid with you. Ask them to push your thinking. There is nothing like talking to a trusted and respected friend to help you see things in a new light.

Lastly, prototype and experiment. As Steve Jobs once said “Your work is going to fill a large part of your life, and the only way to be truly satisfied is to do what you believe is great work. And the only way to do great work is to love what you do. If you haven’t found it yet, keep looking” (source: Steve Jobs Stanford Commencement Address, 2012)

Take as many internships, or new projects as you can. Talk to dozens of people who have careers you think may be candidates for your true “Point Z”. Doing this over and over again, recording your impressions along the way, and you’ll start to discover that things which truly matter to you will repeatedly surface as themes, while things that you thought were important will begin to fade. Treat “finding your Point Z” as you would prototyping & perfecting a product.

Conclusion

And that is perfectly fine. The most meaningful things in life typically require the greatest amount of effort and sacrifice to obtain. Understanding with abject clarity what we want from our life’s career is certainly in this category. It’s worth not simply settling for what is convenient or easy.

As the poet Mary Oliver once said: “What is it that you plan to do with your one wild and precious life?” (source)