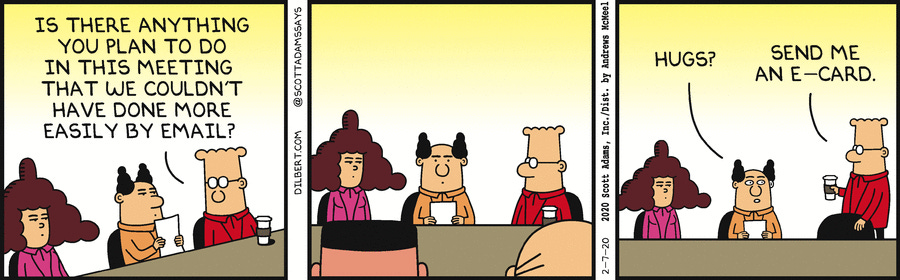

A practical guide on what to do BEFORE a meeting so that you don’t end up running a session that looks like a “Dilbert Cartoon”

An Unexpected Compliment…

A few years ago I had just finished wrapping up a 3 hour executive workshop I had been asked to lead when I found myself being tapped on the shoulder by our CEO. He flashed a quick smile and then said “Thanks for doing this. You’re exceptionally good at running meetings.”

I’ll admit to being caught a little off guard. Being “good at meetings” isn’t something I think most recent MBA grads necessarily aspire to. But after some thought I’ve decided that it’s one of those rarely talked about skills that can mark you as rare/valuable. It’s the opposite of being the person people always dread having in the room. If you want to find yourself in the “room where it happens” it pays to be the person everyone wants to be prepping and running “the room”.

Last week, I wrote about the true cost of meetings, why we seem to be unable to escape them, and why (gasp) meetings may actually still be a very useful (though regularly misused) tool for providing real value.

This week I wanted to get more tactical. This is Part I of our “guidebook” on how to do meetings in a way that will set you apart. We’ll cover:

- What to do before the meeting (Part I) → this week

- What to do during the meeting (Part II) → future article

- What to do after the meeting (Part III) → future article

I hope it’s helpful. Some of this will likely seem common sense. Other things I have found to be surprisingly rare. At the very least, it should prevent you from looking like a Dilbert cartoon.

What to Do BEFORE the Meeting

Principle #1 – Decide “What Type of Meeting Is This?”

All meetings generally fall into 3 buckets:

- Type 1 = “Educate / Inform” Meetings

- Purpose: educate a group on a topic (usually a complicated one) so that everyone is on the same page, or communicate a lot of information to a lot of people in a short period of time.

- Type 2 = “Decision” Meetings

- Purpose: make a decision for the group (usually with input from everyone else) + make sure everyone understands the decision & next steps

- Type 3 = “Brainstorm” Meetings

- Purpose: use the group to come up with a bunch of creative ideas to solve a problem; identify which ideas have the most potential

It’s important to know what type your planned meeting is. Trying to combine multiple types into a single meeting usually ends up being extremely messy because it’s hard to do all of these jobs in a single session.

Just pick one type and stick to it. It gives the group focus. Make it extremely clear to everyone before they even walk into the room or Zoom meeting what type of meeting they should expect (and therefore, what the goal of the meeting is).

Principle #2 – “Could this be an email?”

Before you hit “send” on a meeting calendar invite, ask yourself “do we actually need to talk in person?”. Again, REMEMBER THE COST OF MEETINGS!

Really what you’re asking yourself is “am I willing to spend $X to “educate / inform / decide / brainstorm with a group?”

Oftentimes, there are cheaper ways to get the same outcome:

- If it needs to be timely, would a Slack or Teams chat cover most of it?

- If it’s not super time sensitive, could I send them a quick email to update them instead?

- For bigger decisions and updates, would a Google Doc or other system with collaboration, comment, and editing features better convey the information?

The great thing about all of these options is that they’re asynchronous. This means that everyone has time to review and respond on their own schedule. This can often lead to the same result, but with less cost and stress.

As Silicon Valley investor/entrepreneur Naval Ravikant puts it succinctly:

“If someone wants a meeting, see if they will do a call instead. If they want to call, see if they will email instead. If they want to email, see if they will text instead. And you probably should ignore most text messages—unless they’re true emergencies.”

Principle #3 – Plan the Battle (Make an Agenda!)

One of my biggest pet peeves is walking into a meeting that has no agenda. This usually ends up with everyone verbally meandering until the time runs out. Again, meeting’s have real costs, so have a plan before you walk in so you can spend that “cost” wisely.

Before any meeting, create an agenda that is crystal clear on the following:

- What is the objective of this meeting? (aka, how will we know our time together has been successful?)

- What are the specific items we’re going to answer to answer / make decisions on?

- What are the next steps / assignments that we need to execute after this meeting?

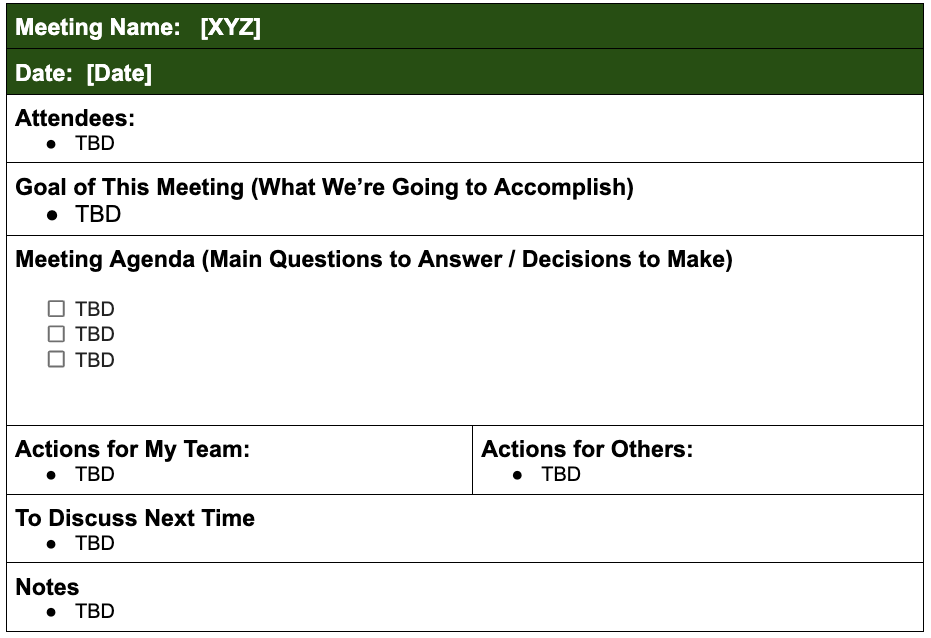

Here is an extremely simple (but effective) agenda template I use regularly:

A few pro tips:

- Send in advance! (at least 24 hours beforehand). Attach it to the meeting invite if you can.

- Limit the agenda (keep it focused). Don’t try to do too much. Better to accomplish a few items well, than cover a bunch of topics haphazardly.

- Take notes during the meeting (especially on decisions & action items). You want your agendas to be a “recorded memory” on what was discussed and decided. This is incredibly useful when trying to remember the logic behind key decisions months later.

- Send the notes after (more on this in a future article…)

Principle #4 – Prep the Invite

Obviously people will need to know when / where the meeting is happening. A few pro tips on sending a calendar invite:

Keep the meeting short: Meeting fatigue is a real thing. No one is going to be excited to show up to something that feels like a Congressional summit. I’ve generally found that an hour should be the maximum slot you should book (with rare exception). 30 or 15 min chats are even better.

Build in buffer time: All of us are subject to Parkinson’s Law (the idea that people will fill the full time allotted to them). And every single one of us has been in situations where we go over time. Stuff happens in meetings, so prep for that. Protect everyone’s schedules by accounting for this beforehand.

For example, plan the agenda to only take 45 mins, even if you have an hour booked. This will give you 15 mins of “buffer” for when Jerry from marketing takes too long to explain why his metrics actually aren’t as bad as they look, or when your CEO brings up an unexpected issue that needs to be debated.

Avoid “Draining” Meeting Times: Be mindful of when to schedule meetings. Want people to be fully engaged? Stay away from scheduling meetings on Friday @ 4:30pm right when everyone is dreaming of the weekend. Don’t be the jerk that schedules over lunches. Don’t schedule a meeting “first thing in the morning” before folks have had the chance to even check their email and get settled/prepped for the day.

Pro tip: if you’re working with people who are building things (engineers, coders, creatives, etc..) keep in mind the “maker vs. manager” schedules so you can avoid disrupting their “deep work” flows (you don’t want to become the boss who is actually stopping people from getting work done).

Find a Room: This kinda seems obvious, but you’d be amazed at how many in-person meetings I’ve been invited to, only to realize at the last minute that no one has remembered to actually book a room for us to meet in. Thanks to COVID-19 we’ve gotten so used to virtual meetings that we almost always assume “virtual” first. Please make it clear where everyone should show up to (and try to snag your favorite conference room in advance)

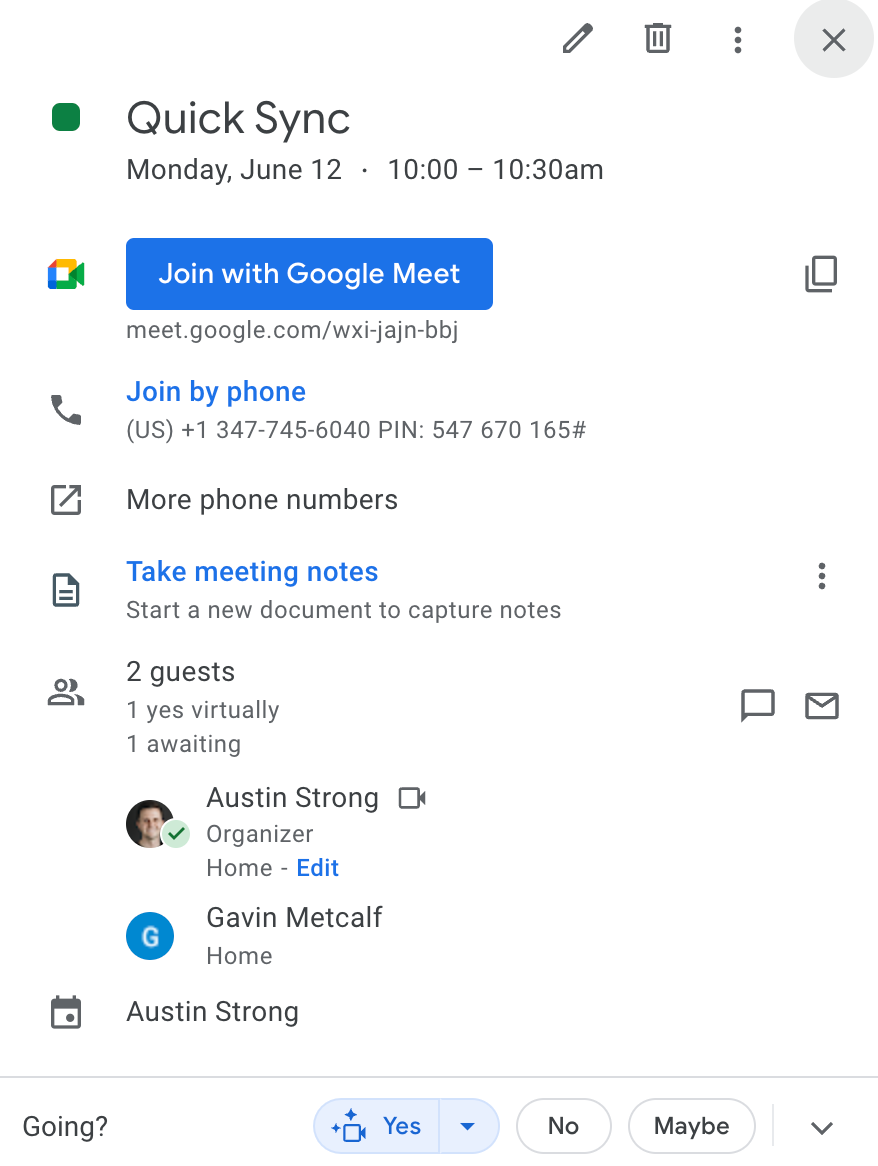

Be Descriptive in the Meeting Invite: This one is a pet peeve of mine. Don’t just randomly throw a meeting on everyone’s calendar that looks something like this:

That’s akin to just sending an ominous “can we talk?” slack message to someone. The person receiving this meeting would have ZERO context on what this meeting is about, where it is, why we’re talking, etc… They’re walking in blind (something that you never want to have happen).

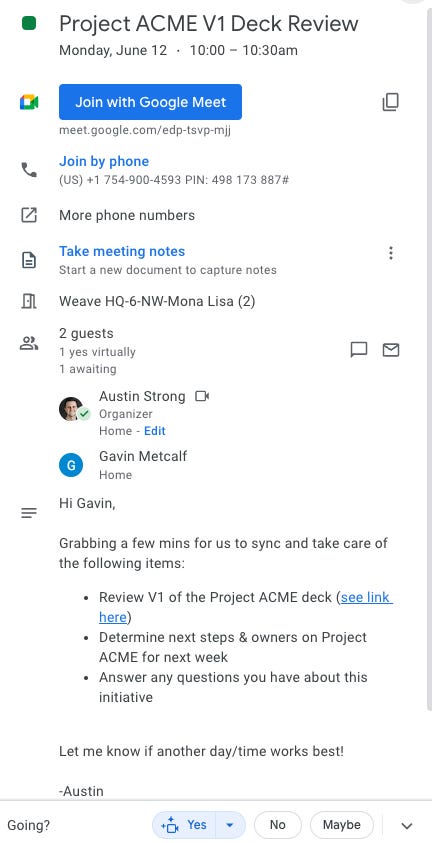

A good meeting invite should have the following:

- A Descriptive Title

- A list of who is attending

- A short (but clear) description of what the meeting is about

- Location / Meeting Room

- Bonus points if you attach the agenda / document (ex: PPT, Spreadsheet) you’ll be reviewing!

Fortunately, most calendar systems like Google/Microsoft make it really easy to send out good invites like this. Here’s an example:

Principle #5 – Pre-Wire Key Stakeholders

If you’re unfamiliar with the term “pre-wiring” I’d recommend reading this deep dive on the subject (something we’ve written on earlier).

In short = you need to remember that your job in any meeting isn’t just to persuade the decision maker or audience. It’s to ensure that the right idea survives and is implemented after you leave the room. That will only happen if the leadership is 100% bought into it. You not only want the CEO to be nodding in agreement, you want every other head to be nodding in agreement as well. And that only happens if you take the time to “pre-wire them”

This means taking the time to meet with each and every one of your stakeholders in advance and persuade them to the idea, so that when that presentation finally hits the CEO’s desk, they’ve all given it their blessing and buy-in.

A few quick tips on pre-wiring:

- Identify the Right Folks: When prepping your idea for presentation, think carefully about who all the stakeholders really are. Think “who else besides the decision maker is going to be impacted by this?” It’s often not the people with fancy titles you need to worry about, but the “boots on the ground” folks who will be tasked with implementing your recommendation (they’re the ones who can really launch your idea or drag their feet if they’re not sold). A great litmus test is to use the questions “whose job will this recommendation impact?” or “who will actually have to implement this idea or change their way of working to accommodate it?” Those are the folks you need to get onboard first.

- Pre-Wire Well in Advance of the Pitch Meeting: Ask to meet with each of these stakeholders (in small groups or even individually). Show them the analysis and the recommendation. Tell them “I’m going to present this to the boss in a few weeks, but I want to get this right. You have an invaluable perspective. What would you add/change? What are we missing?”

- Ask them to participate in the meeting in advance: Ask to do a practice presentation with them. Ask them to co-present along-side you (if possible). Make them feel like this is as much their idea as it is yours. People will defend what they feel like they own. And you definitely want them backing you when pitch day comes.

Last note on pre-wiring: This is especially important for sensitive issues or for “decision” meetings with lots of stakeholders.

Principle #6 – Send a Pre-Read Memo

One of the biggest (yet silent) time wasters in meetings is the sheer amount of time you spend bringing everyone up to speed on a given topic. “Educating” the audience can easily suck up 50-75% of the time, leaving only a few short minutes to actually make a decision, assign action items, or debate a critical issue. This usually results in someone uttering the phrase “let’s find another time to continue this discussion” (aka yet ANOTHER expensive meeting on everyone’s calendars)

The solution to this issue? Enter the “Pre-Read Memo”….

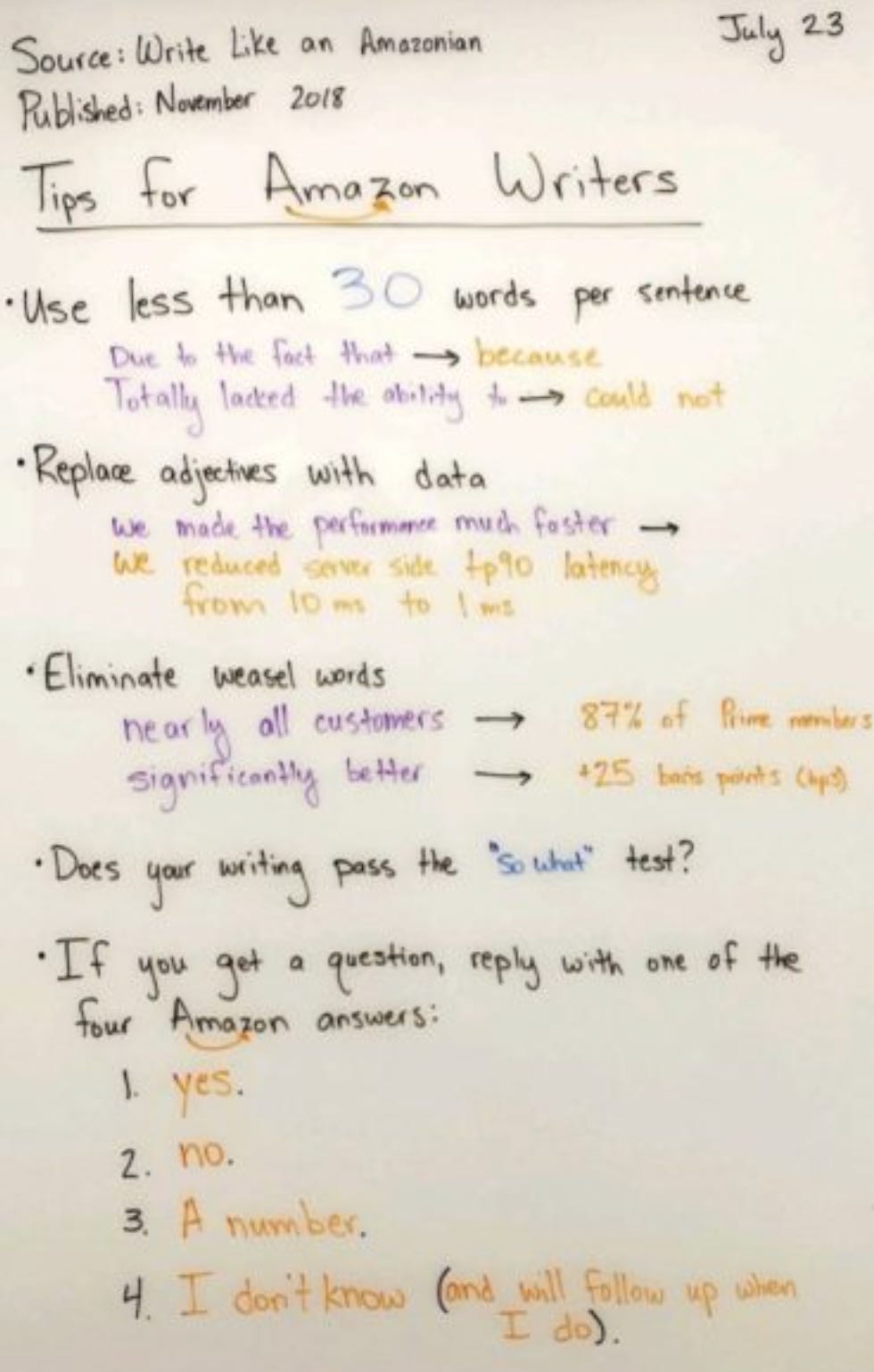

The company most famous for using “Pre-Read Memos” is Amazon. At Amazon, every meeting starts with each attendee silently reading a 6-page narratively-structured memo, before any discussion begins. Participants are encouraged to take notes so they’re ready to contribute once the meeting discussion kicks off.

These memos serve a few key purposes:

- Everyone is on a level playing field, understanding the context, background, key information, and goals for your meeting.

- It forces whoever writes the memo (almost always the person who is leading/driving the meeting) to clarify their thinking. You learn a lot by putting thoughts in writing, especially if you have to write it in a narrative structure

- By reading memos in the meeting, it ensures everyone has read it, even your attendees are busy executives who are in dozens of meetings per week.

One warning on #3 above: Require that folks actually read this (especially if you’re sending it out to be read before the meeting). It can be really frustrating to put a memo together, send it out well in advance, and then show up to the meeting only to discover that no one took the time to even glance at it (which defeats the whole purpose!).

Amazon gets around this by dedicating time at the beginning of each meeting for reading the memo. Most companies struggle to do this, and memo’s need to be sent out and read asynchronously. I’ve often personally sent a Pre-Read memo to consulting clients or internal stakeholders (usually ~1-2 days in advance of the meeting), though I’ll sometimes use a short pre-read PowerPoint deck (usually 5-7 slides) instead of a written memo.

To help get folks in the habit of reading these, you may need to recruit an executive to help enforce the expectation that “everyone reads before showing up” until it becomes part of the team culture.

As a drastic measure, I once asked my company’s executive assistants to block off dedicated time on their C-Team/VP’s calendars so leaders were guaranteed to have time to read the pre-meeting memo in advance of a particularly important meeting.

Last Tip on Memos: Make these memos extremely clear and concise. Amazon has specific guidelines/rules for pre-read memos which I think are excellent advice for any organization:

Principle #7 – Use the 2 Pizza Rule (Decide Who Actually Needs to Attend)

Tell me if this has ever happened to you. You send a meeting invite to 3 others you need to chat with only to watch as more and more people get added to the meeting invite. Soon your small 4-person meeting has ballooned to 15+ attendees.

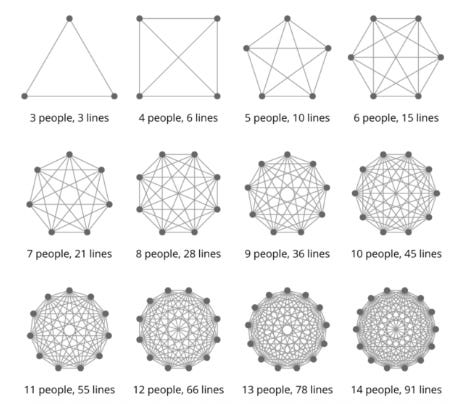

That’s a problem because the larger a group becomes:

- The meeting costs more $$$ (think of the total hourly cost of everyone meeting)

- The meeting becomes more difficult to manage effectively

- Communication and decision making slow down. Remember that complexity grows exponentially as you add more people to a discussion

The primary reason we avoid leaving people out is because we want everyone “in the loop”. This is a bad framework.

So how many people should be invited to a meeting? My favorite rule of thumb is the “2 Pizza Rule”. The basic idea is to never have more people in a meeting than what two pizzas can feed. That usually ends up being ~6-8 people MAX (unless you can eat pizza like I can, in which case you’re probably limited to 3 people).

More than 6-8 people and communication tends to break down, people are in meetings where they don’t speak up or contribute, and you end up wasting a lot of time and money.

When identifying who really needs to be in the meeting, ask the following questions:

- What type of meeting is this? (remember a “decision” or “brainstorm” meeting needs to follow the 2-pizza rule strictly, while a “educate/inform” meeting could have as many people as needed)

- Who really needs to be here?

- Who could be updated/informed afterwards but doesn’t need to attend?

In general: always opt for keeping the meeting small. You can always update those not invited later.

Conclusion

Here’s a summary of what to do before a meeting starts:

- Principle #1 = Decide “What Type of Meeting Is This?”

- Principle #2 = “Could This Be an Email?”

- Principle #3 = Plan the Battle (Make an Agenda)

- Principle #4 = Prep the Invite

- Principle #5 = Pre-Wire Key Stakeholders

- Principle #6 = Send a Pre-Read Memo

- Principle #7 = Use the 2 Pizza Rule (Decide Who Actually Needs to Attend)

The difference between a “great meeting” vs. a “terrible meeting” is often determined by the prep work you put in before the meeting even starts. In my experience, that is effort worth putting in. You’ll be a more effective leader if you’re able to use meetings for their true purpose: bringing smart people together to make good decisions.

Being known by others as “the best person at running meetings” isn’t necessarily the most important thing for your career trajectory. However, it is one of the ways in which you can distinguish yourself from the crowd. You want to be “rare” in as many ways as possible. And being good at meetings is a very easy way to win what I call the “margin victories” (the small things that cumulatively make a big difference)

If anything, I hope these principles help you prevent more Dilbert Meetings from happening…

Note: We’ll cover what to do DURING and AFTER meetings in Part II and Part III of “The Unwritten Guide to Running Meetings that Don’t Stink” (future articles)