A practical guide on what to do DURING a meeting so that you don’t end up running a session that looks like a “Dilbert Cartoon”

The Problem with Brain Golfing…

Have you ever been talking to someone only to realize that they’ve been completely zoning out for the last few minutes and haven’t caught a word of what you’ve said? That happened to me in one of my first consulting engagements. We were presenting a plan to revamp a struggling e-commerce warehouse to the local manager. About 5 minutes into a detailed (and extremely beautiful) Powerpoint presentation we stopped to ask what his thoughts were on the proposal.

He looked up, refocused his eyes, and said “sorry, what was the question again?”

It was that moment when I realized that his business was in serious trouble. He was completely vacant mentally when it came to critical discussions around day-to-day decisions. I noticed it more and more in the following weeks. Needless to say “Brain Golfing” is not a fast track to promotion (the manager was fired only a few weeks after our engagement had ended).

You’d be surprised at how few people run meetings well. Up to 71% of senior managers feel that their meetings are unproductive. That is a seriously low bar for you to clear and “stand out from the crowd.”

Being known by others as “the best person at running meetings” isn’t necessarily the most important thing for your career trajectory. However, it is one of the ways in which you can distinguish yourself from the crowd. You want to be rare in as many ways as possible. And being good at meetings is a very easy way to win what I call the “margin victories” (the small things that cumulatively make a big difference).

This is Part II of our “guidebook” on how to do meetings in a way that will set you apart (and avoid feeling like you’re part of a Dilbert Comic). Here’s what we’ve covered so far…

- Prelude: The True Cost of the Dilbert Meeting → prior article

- What to do before the meeting (Part I) → prior week

- What to do during the meeting (Part II) → this week

- What to do after the meeting (Part III) → future article

Today, we’re covering what to do DURING the meeting, so you can take advantage of all the solid pre-work and pre-wiring you’ve put into making sure your meeting is a success.

Or as American WWII general George S. Patton said:

“The best plans are useless if they are not executed.”

Let’s dive in….

What to do DURING the Meeting

Principle #1 – Assign the 4 Meeting Roles

One of the absolutely worst things that can happen in a meeting is to show up and realize that no one is really in charge.

In those settings the conversation quickly turns into what I call “school project syndrome”; everyone is spouting out ideas, raising questions, going down rabbit holes, and generally talking in circles. Then someone notices that time is almost up, and everyone leaves the room with no tasks assigned, no sense of organization, and frankly little confidence that any action is going to result from the last 45 minutes you all spent together.

This is why school projects are so frustrating. No one is usually willing to step up and be the leader, and so you all spin your wheels until the terror of the deadline forces you to cobble some sort of a hasty project together (which you pray will get you a good grade).

Meetings need leadership. But the best run meetings I’ve ever attended actually have 4 distinctly assigned roles:

- The Decision Maker

- The Conductor

- The Advisors

- The Informed

Here’s a brief explanation on each one…

The Decision Maker: This is the person who actually has the decision making power. He/She has the ultimate go/no-go vote on any item being debated. Harry Truman (former U.S president) famously had a sign on his desk that said “The Buck Stops Here”, clearly sending a message that he ultimately bore the responsibility (and authority) for any decisions that came across his desk.

The Decision Maker is ideally the one who sets the agenda and leads the meeting, but I’ve been in situations where they actually allow others to guide the discussion (more on that in a moment). But a good Decision Maker knows when to insert their voice & authority, and when to let the room debate in order to surface the best possible solution. But they do need to make it clear when they’ve made a decision. The worst thing a Decision Maker can do is to let everyone leave the room without clarity on what the next steps or decision is.

You need to identify this person well in advance of the meeting and make it abundantly clear to everyone else who the real decision maker is. If you don’t you’ll quickly find yourself stuck in “school project syndrome”. If you find yourself in a situation where it’s obvious that no one knows who the Decision Maker is, pause everything and ask the hard question: “who really owns this meeting / decision?”. Until that is cleared up, nothing else in the meeting matters.

The Conductor: This is the person who is the “right hand” of the Decision Maker. Think of them as the COO of the meeting. In music, a symphony conductor is the one who keeps all the musicians working together in harmony off of a single sheet of music. They prevent everyone from going “off track”. An effective meeting Conductor does the same thing, just in the corporate world.

This is the person who acts as the referee of the meeting (telling people when they need to stay focused on the topic at hand), takes the notes/action items & sends them out to everyone afterwards, makes sure the agenda starts/ends on time, and in general keeps the trains running on time.

It is possible for the Decision Maker and the Conductor to be the same individual, but I’ve found that it can be quite effective for those roles to be distinct.

Again, it’s important to inform everyone in advance who is going to be playing this role. It can be as simple as saying “Susan is going to ensure that this meeting stays focused and on task” before the meeting starts (which then gives Susan the authority to tell the room they need to get back on track if they start going off on a tangent topic).

A good Conductor will also help remind the Decision Maker to summarize the key action items and decisions at the end of the meeting. This gives the meeting closure and is especially helpful in reminding everyone what the key takeaways are.

The Advisors: These are the folks in the room who are the “subject matter experts”. Their role is to give input, provide insight into special areas, and generally to advise the decision maker. They are often members of the team who may be assigned to carry out tasks decided in the meeting by the Decision Maker. These are the key stakeholders who have a voice in any decision being discussed. The majority of people in a meeting usually fall into this category.

Think of an Advsor like the people assigned to serve in the Cabinet of the United States. The Cabinet (the Advisors) provide insight and key points to the President (the Decision Maker) while the entire discussion is kept organized by the President’s Chief of Staff (the Conductor).

A good Advisor shouldn’t try to dominate the discussion, but provides key insights when they are (A) asked, or (B) they clearly have something unique to say. These folks often have the deep expertise in given areas needed to inform an important decision, but they may not have the whole picture.

The critical thing for any Advisor is to remember that they are NOT the Decision Maker. I’m generally against deciding things by committee, and you need to be wary if you’re an advisor that you don’t try to become the Decision Maker (otherwise you’ll end up with the “too many cooks in the kitchen” problem of everyone trying to be in charge). There are instances in which the Advisors may be asked to vote on a solution, but again, I generally recommend that any well-run meeting have a single person in charge.

The Informed: These are folks who don’t actually need to be in the meeting! They don’t need to make a decision, organize, or advise. They simply need to have the decision/information discussed in the meeting communicated to them afterwards! This can often be done via an email (or other forms of asynchronous communication).

If you know someone doesn’t have anything to contribute in the meeting and simply needs the info, save them (and yourself) the time and cost of having them attend. Make it clear that they’ll receive the needed info from the meeting itself, but that they aren’t going to be asked to attend.

You want to keep meetings as small as possible (remember to follow the “2 Pizza Rule”)

Principle #2 – Use the Kumquat Rule

The second most dangerous snare to any meeting is the “gravitational pull of the rabbit hole.”

We’ve all been in this situation: a conversation is happening when someone in the group raises a question that’s not really on topic. Before you know it, 15 minutes have gone by and the discussion has completely regressed into a mess of opinions, diatribes, and debates that are completely off the mark.

These kinds of tangents are productivity killers. Even though they may be well intentioned, most meetings have one (or more) people who have a bad habit of straying too far from the agenda. Even experienced Conductors can have a hard time reigning such people in and keeping everything on track.

One of the best solutions I’ve found to this particular problem is the use of a “code word”. This is a pre-agreed-upon word that, when spoken, is a clear signal to the room that the meeting has gotten too far off topic and needs to get back on point. Simply put: It’s a way of telling someone to get back on track without being rude.

A few years ago I implemented a “code word” (Kumquat) at my current company. We empowered anyone, no matter how junior or senior, to say “Kumquat” at any point in any meeting. I’ve been amazed to see how quickly this has caught on. It’s even become a verb!

Just last week, one of our top executives noticed that we were spending too much time on a topic and said “I vote that we Kumquat this topic right now, and discuss this offline”. Even people new to the company have started to pick up on what’s becoming famously known as “The Kumquat Rule”. It’s saved us hours of verbal wandering, and is actually quite fun to use.

A few tips on implementing a good “code word”

- Choose a code word that is funny, memorable, and catches the attention of the group when it’s used. I’ve been on teams that have used code words like “Bananas”, “Shenanigans”, “Batman”, and “Kumquat”. One of my favorites is ELMO (enough, let’s move on)

- Tell everyone before the meeting what the code word is and how it works.

- Encourage people to use the “code word” often. It does no good to set up a code word, and then just go down the tangent without using it. If you’re leading a meeting, set the example by using the code word often. It will set the tone and let others know they really can use it as well. You want the habit of squashing tangents to become cultural.

- If a tangent raises an important point, quickly “Kumquat” it, but be sure to quickly schedule an offline chat (or slack/email) to follow up on it. You don’t want to ignore important tangents, but you do want to protect the goal of the meeting you’re in.

Principle #3 – Start / End on Time (and use a buffer!)

No one likes meetings that start 10 minutes late because people are still filing in the room or take way too much time doing the usual small talk.

People equally hate meetings that run way over time and cause them to be late for other appointments.

What you want to do is establish a culture of “we start/end on time, no matter what.” This shows that focus (& everyone’s time) are highly valued.

A couple of tips on how to do this:

Start the meeting (even if not everyone is there):

One CEO I’ve worked for is extremely good at this. He shows up to every meeting ~2 minutes early, and the moment the clock strikes the meeting time he says “should we get this thing started?” (clearly sending the signal that it’s time to kick things off). If folks still aren’t in the room, he asks us to go ahead and start anyways. After doing this for a few weeks, people quickly got the hint and stopped showing up late.

This means that if you’re running the meeting, it’s a good idea to get there at least 5 minutes early (or more) to get everything set up and ready to go once the clock hits the starting time.

Build a Buffer: Plan to end the meeting ~5-10 minutes early

All of us are subject to Parkinson’s Law (the idea that people will fill the full time allotted to them). And every single one of us has been in situations where we go over time. Stuff happens in meetings, so prep for that.

For example, plan the agenda to only take 45 minutes, even if you have an hour booked. This will give you 15 minutes of “buffer” for when Jerry from marketing takes too long to explain why his metrics actually aren’t as bad as they look, or when your CEO brings up an unexpected issue that needs to be debated.

Side note: If you accomplish the objective of the meeting early then end it early! We’d often get made fun of in consulting for using the phrase “I’m going to give everyone a few minutes back” (but I never heard of anyone complaining about a meeting that ended earlier than expected).

Principle #4 – Use a “Wrap Up Routine”

Save the last 5 minutes of the meeting to do what I call a “Wrap Up Routine”. It goes something like this:

- Quickly summarize all of the assigned action items, owners, and due dates

- Quickly summarize the key decisions & insights from the meeting

- Let everyone know if you’ll be scheduling a follow up meeting (and approximately when that will be)

It sounds simple, but you’d be amazed at how much something like this helps. I’ve been in way too many meetings where the discussion abruptly ends because time is up and everyone leaves the room without really making sure that a decision was reached or an action was assigned. Then everyone is shocked when next meeting there still isn’t alignment or action taken 🤦

Bonus points: the Conductor should send a written summary of the meeting assignments, decisions, and notes to everyone after they leave (so you get a verbal confirmation + a written confirmation).

Principle #5 – Use the Agenda as Checklist

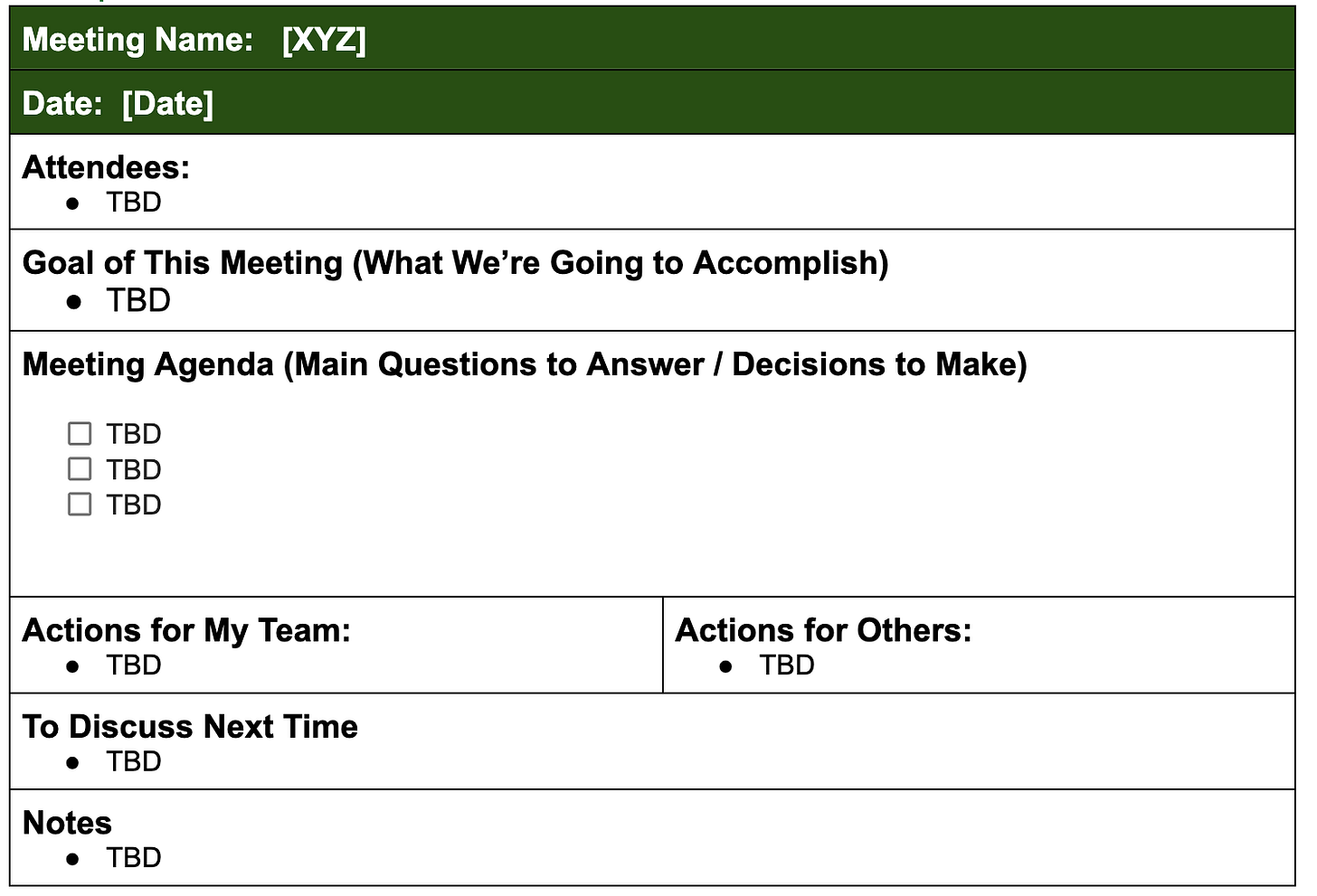

Before any meeting, create an agenda that is crystal clear on the following:

- What is the objective of this meeting? (aka, how will we know our time together has been successful?)

- What are the specific items we’re going to answer to answer / make decisions on?

- What are the next steps / assignments that we need to execute after this meeting?

Show the agenda on the screen when running the meeting and literally use it as a checklist as you work your way through it (I personally love crossing things off as we tackle them, as it gives everyone a sense of progress)

Here is an extremely simple (but effective) agenda template that I use regularly:

Ensure that your meeting’s Conductor takes detailed notes on what happens during the meeting. People have fickle memories, and you want to have a clear record / documentation of what happened.

Detailed notes are better than “shorthand notes” because many folks may need to reference these later and it provides a historical log for how the discussion progressed. I’ve been saved more than once by going back to old meeting notes and remembering “oh THAT is why we decided XYZ”.

Principle #6 – Bring Your Brain

This one is simple: You can only be in one place at one time. People can multitask, but it is impossible to multi-focus. If you’re showing up to a meeting, you should actually be there to provide value, and you can’t do that if you’re “brain-golfing” or trying to take care of other tasks.

Participate and make yourself heard (but please don’t just talk for the sake of talking). Meetings can be incredibly productive (but expensive) uses of people’s time, and you don’t do any favors by showing up and adding nothing.

If you’re multitasking during a meeting, it’s a clear sign that you don’t really need to be there (aka, you should be in the Informed role) OR that the meeting is not providing value OR that it’s not being run properly. Any of these 3 warrants a discussion or a decision from you (ex: “does the person multitasking really need to be here?”)

Don’t allow yourself (or others) to multitask. One of our executives has a habit of asking everyone to turn off their phones & laptops for each key meeting she runs. It may seem extreme, but it’s been very effective and driving participation and value up.

Hot Take: Don’t be offscreen when you’re attending a remote meeting (ex: Google Meet or Zoom). It sends an implicit signal that you’re doing something else and aren’t really paying attention.

Conclusion

Here’s a summary of what to do during the meeting itself:

- Principle #1 = Assign the 4 Meeting Roles

- Principle #2 = Use the Kumquat Rule

- Principle #3 = Stand/End on Time (and use a buffer!)

- Principle #4 = Use a “Wrap Up Routine”

- Principle #5 = Use the Agenda as a Checklist

- Principle #6 = Bring Your Brain

If you need a refresher on what to do BEFORE the meeting starts, check out Part I. We’ll cover what to do AFTER meetings in Part III of “The Unwritten Guide to Running Meetings that Don’t Stink” (future article).

And remember, just because most meetings you’ve been in have stunk so far, doesn’t mean yours have to…