What we can learn from Genghis Khan, Google’s CEO, and Kobe Bryant about when to “step on the gas” vs. “take it easy”

The Thing that Worried Genghis Khan…

According to legend, nearing the end of his life, the great Genghis Khan, founder of the largest empire in history, took his sons and grandsons back to the harsh and rugged Mongolian homeland to teach them a lesson he felt was critical for the survival of the empire.

Overlooking the barren steppes that stretched out as far as the eye can see, the great Khan asked each of his posterity to look closely at the humble tents of the nomadic tribes who still lived there.

Genghis reminded his family that the Mongols hadn’t always been the unstoppable force that had brought the great kingdoms of China, Persia, and Russia to their knees. For centuries they had been nothing more than a loose confederation of tribes, eking out a living as pastoral nomads on the unforgiving plains of Central Asia. They had no cities, no written language, and no grand monuments – just their horses, their yurts, and an obsession with mastering the bow & arrow. They were poor, unkempt, and disdained by the “civilized kingdoms” who were their neighbors.

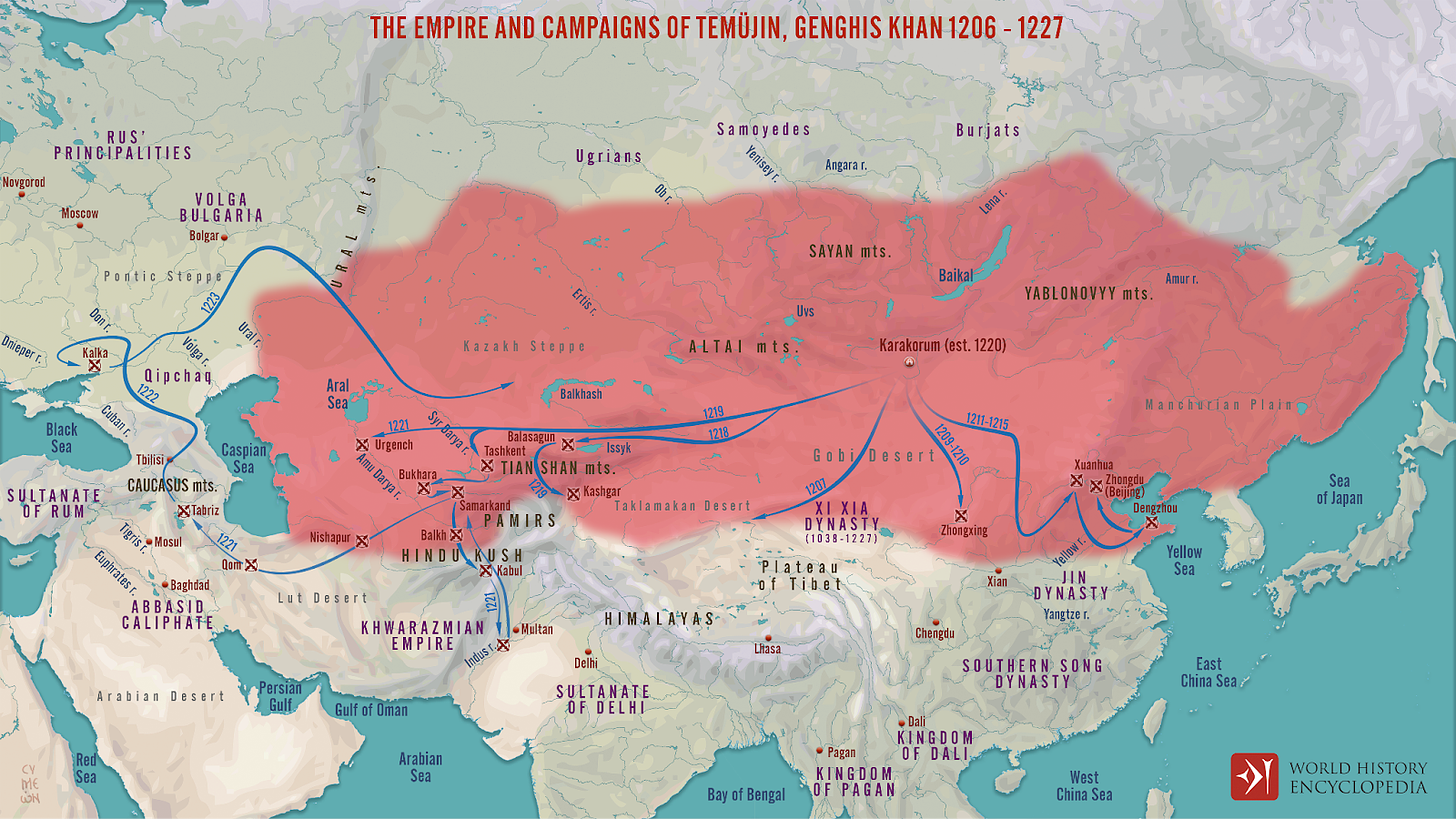

But over the past 20 years, Genghis had taken those ragged groups of horsemen and forged them into the most terrifying army the world had ever seen. The Mongols, under Genghis’s leadership, exploded out of their homeland like a storm that no one saw coming. They smashed through the Great Wall of China, reducing entire cities to ashes, conquering the powerful Jin Dynasty in the process. And they didn’t stop there. They swept west, across the Silk Road, into Central Asia, the Middle East, and even Eastern Europe.

Their conquests were swift, brutal, and precise. The Mongols had no match when it came to mobile warfare. Their mastery of the composite bow, their lightning-fast cavalry maneuvers, and their uncanny ability to adapt to any environment made them nearly unstoppable. They didn’t rely on the slow, heavy armies of medieval Europe or the great walled cities of the Islamic world. The Mongols were more like a swarm—always moving, always unpredictable.

But the great Khan believed that his people had a secret to their success; a capability he was now deeply worried his sons and grandsons would forget and ultimately lead to the loss of the empire they were now richly enjoying: their infamous “Mongol grit”.

The Mongols had been a people whose survival in the brutal central Asian steppes depended on their willingness to do things no “civilized” person would do (as one example: Mongol horsemen were famous for their ability to spend up to a week in the saddle with little to no rest or food, even drinking the blood from a small cut on their horses neck as they rode to sustain themselves).

Genghis told his sons and grandsons that if they allowed themselves to become “soft” like the people they had just conquered, they too in turn would soon find themselves defeated by people who had not forgotten what it meant to be gritty. They couldn’t permit themselves to become comfortable with their new found riches, walled cities, or easy wealth.

The Khan decreed that from that point onwards the princes of the empire would be required to spend their youths back in the harsh Mongolian steppes among the nomads where they would train and learn the ways of their ancestors, lest they ever forget what had given them the chance to become princes in the first place.

It was perhaps with this story in mind, that the French philosopher Voltaire said:

“History is filled with the sound of silken slippers going downstairs, and wooden shoes coming up”

A Modern Day Mongol Problem…

The reason I started thinking about Genghis Khan’s worry is because a few weeks ago, Eric Schmidt, ex-CEO and executive chairman at Google, made headlines for expressing a similar fear.

Schmidt, who left Google more than 5 years ago, was speaking at Stanford University and stirred the proverbial pot when he was asked why Google was losing the artificial intelligence (AI) race to competitors like OpenAI.

Schmidt responded:

“Google decided that work-life balance and going home early and working from home was more important than winning. The reason startups work is because the people work like hell.”

It wasn’t quite as eloquent as Voltaire’s statement, but the meaning was the same. Schmidt’s view is that great companies, like great empires, have to maintain the “edge” that made them great in the first place. Otherwise they will quickly find themselves replaced.

His comments have since sparked an enormous online debate about the AI arms race, Google’s ability to compete against other AI players, work-from-home policies, and whether or not the current generation of Google employees is too “soft” or not.

But that’s not what this article is about.

There are people far more qualified than me to discuss artificial intelligence and Google’s place in that race.

I’m also not interested in simply ending with a simple and too-obvious statement along the lines of “people & companies always need to be wearing their “wooden shoes” and #outhustle the competition”.

I say that, because I don’t think that’s fully the right answer.

My gut tells me that there’s actually a bigger question to ask here, one that ordinary people like you/I wrestle with every day: “Is there a right time to wear the silk slippers vs. the wooden shoes?” or is success of any kind always dependent on a constant willingness to do things other people simply won’t?”

The Cost of Wooden Shoes…

The idea of always being in #grit mode is a tempting one.

We romanticize it with stories like the one I shared above, in movies about great heroes, kingdoms, companies, inventors and entrepreneurs. We look at men and women who work 24/7 for a dream that is important to them with great admiration. Stories about our ancestors who made enormous sacrifices to build a better life are ones that we gladly pass onto our own children in the hope that they’ll latch onto the themes of resilience, work ethic, and toughness in the face of challenges.

And there is simply no denying that Voltaire was likely right. Greatness does not come easily.

As a fan of NBA basketball, I’ve always been struck by stories of players like Kobe Bryant who became famous as much for their willingness to do things that others simply wouldn’t. As one example:

During the run-up to the 2008 Olympics, Kobe did full predawn workouts before official practices started. Chris Bosh and Dwayne Wade (fellow members of the “Redeem Team” Squad) later recounted: “We’re in Las Vegas and we all come down for team breakfast at the start of the whole training camp,” Bosh said. “And Kobe comes in with ice on his knees. He’s got sweat drenched through his workout gear. And I’m like, ‘It’s 8 o’clock in the morning. Where is he coming from?’” Wade added, “Everybody else just woke up. We’re all yawning, and he’s already three hours and a full workout into his day.”

When a fellow NBA player once asked Kobe why he was training with such a brutally early / long schedule, Kobe replied.

“I saw you come in and wanted you to know that it doesn’t matter how hard you work, I’m willing to work harder than you.” (source)

But in these obviously inspiring stories, we often overlook the cost. Working at such an obsessive level, especially over prolonged periods, comes with a price.

But why is this?

First: We don’t have the stamina to wear Wooden shoes 100% of the time

Voltaire’s shoe metaphor doesn’t refer just to the wealth and work ethic of the shoe’s owners, but also the fact that they’re quite uncomfortable to wear. Working long hours, being constantly paranoid about the competition, and putting in the “extra mile” day after day, eventually wears on us. Humans are generally not designed to run a proverbial marathon for decades on end (and in the case of empires or companies, much longer).

This is something I experienced first hand when I worked as a management consultant. The hours there were long and grueling. 60-70 hour weeks were the norm. There was immense pressure created from the “up or out” culture that consulting firms are notorious for. While this definitely generated great results (and accelerated my career), it also had a human cost. I learned soon after joining that less than 8% of those who started at the firm would ever last long enough to make it to the partner level. The typical length of employment for most consultants at the firm was 2-3 years before they left for something that allowed for a more sustainable pace. Some didn’t even make it a year.

When it comes to our careers we should think of them more as a series of sprints rather than a marathon at which we are expected to maintain a 5-min mile pace the entire time.

Famous Silicon Valley philosopher / investor Naval Ravikant said it best:

“Nobody really works 80 hours a week. This is where the mythology gets a little crazy. People who say they work 80-hour weeks, or even 120-hour weeks, often are just status signaling. It’s showing off. Nobody really works 80 to 120 hours a week at high output, with mental clarity. Your brain breaks down. You won’t have good ideas.

The way people tend to work most effectively, especially in knowledge work, is to sprint as hard as they can while they feel inspired to work, and then rest. They take long breaks.

It’s more like a lion hunting and less like a marathoner running. You sprint and then you rest. You reassess and then you try again. You end up building a marathon of sprints.” (source)

In other words, we need to have moments of relaxation, slower pace, and recovery (aka “putting on our silken slippers”) if we’re to survive the long journey.

Second: We start to lose our enjoyment of the things which make us human

This is perhaps the more important point. When you live a life that is always centered around the extreme, doing things that no one else is willing to do every day of the week, you begin to lose touch with the rest of society. It becomes difficult to relate to others who don’t view the world in the same way you do. Because you never “stop to smell the roses” you start to stop spending time with the things that actually add meaning to life: music, art, play, creativity, or the quiet pleasure of a relaxing conversation with a loved one.

These things, though not “grand” or “impressive” on the surface, are the things that those who wear silken slippers understand. They know that humans are not made solely for work, but also to enjoy the fruits of labor. After all, what is the point of gaining wealth, power, or influence if you never actually enjoy the benefits that those things provide? This would be like building enormous wealth through diligent saving + investing, and then never spending a cent of your fortune.

And as we’ve written about before: It’s actually foolish to try and build a “legacy”.

This is perhaps what I find most tragic about those who spend enormous time and effort to accomplish incredible things, but end up neglecting the simple things that life is actually about.

As an example, Kobe Bryant (a classic “wooden shoe” wearer) was onced asked if he had any friends given his intense personality, edge, and work ethic. His response was both inspiring and saddening at the same time:

Q: “So how much are you willing to give up? Have you given up the possibility of having friends? Do you have any friends?”

Kobe: “I have “like minds”. You know, I’ve been fortunate to play in Los Angeles, where there are a lot of people like me. Actors. Musicians. Businessmen. Obsessives. People who feel like God put them on earth to do whatever it is that they do. Now, do we have time to build great relationships? Do we have time to build great friendships? No. Do we have time to socialize and hangout aimlessly? No. Do we want to do that? No. We want to work. I enjoy working.” (source)

It’s not for nothing that we say “it’s lonely at the top”…

When to Wear Wood vs. Silk shoes?

To be honest I don’t have the full answer here. It’s a question I’m still wrestling with.

It’s obvious that wearing silk shoes too often leads to disaster. People get relaxed. Quality begins to slip. Strength is lost. Competitors pass us by. And eventually, empires, companies, and careers can get derailed. We all learned this as children from Aesop’s fable of the Ants & the Grasshopper. We need to have time, even a significant majority of our time, that we are engaged in doing the hard work of building.

But I’m increasingly becoming skeptical of the mythology that has arisen around the belief that greatness can only be built by wearing nothing but wooden shoes. And even if that is true, perhaps we need to consider if that kind of greatness is even worth building in the first place.